It was just me and the carrion beetles for several hours under the unseasonably warm sun of April. As I got burned by the rays, the beetles dove deeper into the subject of our mutual interest—a dead raven. It is so seldom that we see dead ravens and the opportunity to study one cannot be passed up. I brought a bag full of clay, tools, sketchbooks, wood bases, wire, pencils, a chair, and a tripod; thirty or so

Field sketch of dead raven killed by a poacher. Pencil on paper.

pounds of gear for the half-mile walk from the house to the raven’s side. My outing was matched with equal parts opportunistic curiosity and onerous disgust. This raven did not die of natural causes, it was shot. The first thing to meet this fate this year was a rehabilitated great gray owl, then a golden eagle, then this raven, and another and possibly a second eagle; illegal, senseless, and disrespectful in the extreme. The poacher still has not been caught but enough people are watching now that we hope the body count will not increase further. With the tribal elk and

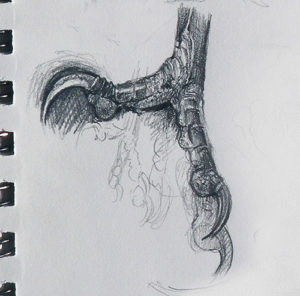

Field sketch detail of dead raven’s claw. Pencil on paper.

bison hunts lasting long into March, there was an abundance of carrion and apparently, “targets” for some unscrupulous twit.

“The very least I can do,” I thought, “is to learn something from this poor bird,” as a way to give it life beyond its days in bone, muscle and feather form. Though no art is ever a substitute for the true, miraculous beauty of something like a living bird, I hope that what I do here will bring some measure of good to this foul situation. The very least that could be done here is to pay homage to those anything-but-black feathers tinted in iridescent purples blues and greens, and to obsess over the stunning architecture of those delicate talons and stout beak. Ravens can live into their twenties in the wild and this could possibly be someone’s husband or wife—they mate for life; this sort of thing should not go unnoticed…