The first thing you notice is the claws. Like five slender piano keys against the backdrop of ebony and brown grizzly fur, they grip one’s attention like an industrial magnet. Far from menacing now, they are objects of exquisite beauty and curiosity. Sadly though, the opportunity to see these impressive claws up close comes only because the bruin is dead. What causes the death of a grizzly bear?

Washed up on the cobbled beach of an island in the Yellowstone River, he lies before us in pristine condition. Aside from some missing hair on his rump, he shows virtually no signs of decomposition. There is no bad odor and his silver-tipped fur still flickers in the wind with the latent breath of life. Perhaps due to the cold waters of the river and the absence of scavengers, it looks as though the bear is asleep, or maybe anesthetized, as bears seldom sleep on their sides.

The death of a grizzly bear provides a rare chance to be in the presence of one of North America’s largest carnivores; despite being post mortem, this is a great privilege. The moment I heard about this bear from a friend, I needed to have a look, even if it meant strapping on a lifejacket and floating down the flooding river to do so. In over two decades of hiking and wandering the Park and surrounding areas, I have only ever found two dead bears. Luckily, a friend with a raft offered to ferry myself and four inquisitive others down to this spot, saving me the swim.

His strong arcing cutlery, the front nails, measure 3 3/4 inches long and must have marked thousands of miles of trails during his lifetime in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. He too, is marked. With two round, red ear tags, he was known to researchers as bear #394, an adult male who made it to an extraordinary 25 years of age. Originally captured and marked in the Bridger-Teton National Forest for dining on domestic sheep at the age of 5, he was then released in the Shoshone National Forest and later roamed and denned the Mt. Washburn and Hayden Valley areas of Yellowstone without incident, according to Kerry Gunther, Bear Biologist for Yellowstone National Park.

From my examination of fresh wounds to his face and head, he died from a conflict with another, stronger bear. Blood issuing from his nose and the fact that his right eye, swollen shut and large as a hen’s egg, supports these suspicions. I estimate his weight at 450lbs; at last capture, Gunther reported that he weighed 524.

Some of the most fascinating revelations that come from close contact with an animal like this are the subtle things—signposts of their individuality and personal traits. A patch of hair about the size of a large, oval pancake on his left forearm is worn down and a slightly darker color. This sort of thing can be missed not only by the casual observer, but even by closely focused eyes. Bears are typically southpaws and they sometimes use their dominant, left forearms like accessory plates or tools to manipulate objects or food as they eat. Bears feeding on whitebark pinecones can sometimes be identified miles from pine forests by the resinous sap covering this discrete patch on their front limbs.

Measuring the front paw

Worn canines

Measuring the hind feet

It is hard to know to where this bear met his fate. Maybe he died along the shores of the Lamar River, the Gardner, or any number of smaller tributaries upstream. At just four days after the peak runoff, he could have come from almost anywhere.

Dried blood stains around his face and eyes—his final wounds—suggest he hadn’t been drifting for very long; that blood would have been washed off completely otherwise. A look at his teeth is telling too; stained, yellow, and rounded off, his canines are worn down to half of their original length indicating a long life. Furthermore, 394 has no remaining incisors on the front of his upper jaw, and only remnants of ones on the lower.

He lived an extensive life in the protected areas in and around Yellowstone where it is not unusual for bears to live into their twenties. The oldest on record, a male, lived to 31, Gunther states. Outside the park, bears seldom make it beyond 15—because of us. As for this individual ursid, the stories he could have told would have been dazzling. Some members of our small gateway community insist that this bear hunted bighorn sheep lambs on the slopes of Turkey Pen Peak, that he was the bruin filmed repeatedly in a ‘downtown’ Gardiner backyard each fall, or that he was one of the stars of the annual spring ‘drowned bison extractions’ that happened at Blacktail Ponds east of Mammoth Hot Springs or maybe he was the bear that we navigated around with our costumed children on dark Halloween nights along the back streets of candy land. Maybe he was all of these or maybe he was none of them. And this is where the special sauce of wild places is sweetest, the possibilities are infinite.

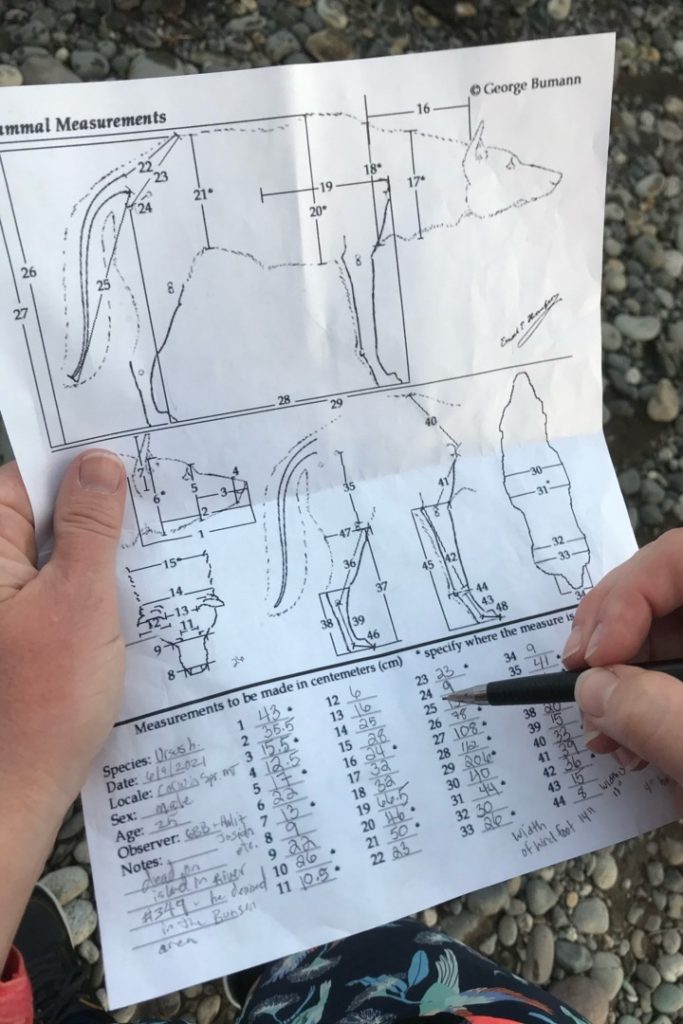

Before leaving him, the artist part of me takes a series of 50+ body measurements for later reference. While these measurements will be useful in developing future sculptures, it is clear that the real impact is not in any kind of data, but rather in the imagination.

Missing upper teeth and greatly worn lower incisors

Calipers and tape used to measure proportions

Record of grizzly bear measurements for later use in the studio

As I lift his weighty arm, I feel its bulk. How many elk calves have these paws swatted to the ground, how many waters plied, adversaries subdued, how many mates gripped and ornery bison sidestepped? I think of watching a new, ‘cub-of-the-year’ wrestling with its mother earlier that morning. What a gift it is to know that since the time 394 was that age, he was able, mostly, to live a life as the elements dictated. Alien (researcher) abductions aside, he was allowed to live on his own terms within the contiguous 48 states of America.

His death came as did his birth—naturally. The fact that this is a rarity says as much about us, as it does about him. As I write, he is understandably being moved by Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks officials so no one can steal his skull, claws or pelt and so that the rest of him may decompose back into the earth he rose out of.

In an era where the truth and myth can be as murky as the turbid Yellowstone waters flowing around our sandled feet, this is as real as it gets. Running our fingers over the powerful forms of an elder from another species on the braids of the longest, undammed river in our nation, is a poignant reminder. Wild lands and wilderness settings are a blessing to us all. Rest in peace old fella, and perhaps some day soon you will be reborn in a sculpture…

Want to read more about Yellowstone grizzlies? Check out: Grizzly Bear Behavior on a Carcass, Following Grizzly Bear Tracks, Courting Grizzly Bears, and Capturing a Grizzly Bear and Wolf Interaction in Sculpture.

Visit my gallery to see sculptures inspired by individual Yellowstone grizzly bears.

Interested in tuning in to animal language to find more wildlife? Start here.

Images © George Bumann/A Yellowstone Life