You can imagine my excitement when I got a text message from a friend innocuously asking, “are you local?” The meaning surrounding this line of a text is, “if you can, you better get your ass over here fast. But if you can’t, no big deal, this probably won’t turn into anything anyway…”. I was local, and I dropped everything at the chance to see to the unseeable.

I have followed the tracks of cougars in Yellowstone so many times without seeing them that it is easy to question whether they actually exist. Shaded range maps in books tell us that the mountain lion—Puma concolor—can be found from just above the U.S./Canadian border, into Mexico, down through the isthmus of Panama, and all the way to Cape Horn at the tip of South America. Once the most widely distributed mammal in the western hemisphere (and despite having been eliminated from around 2/3 of their range), their north-to-south spread still commands a mighty swath of New World geography. And despite extensive incursions by human development into lion habitat, these cats are on the rebound. With cougars seemingly everywhere in these growing strongholds, the question naturally arises, how many have you seen? Don’t feel bad if you claim a big goose egg: you are not alone.

Finding Cougars in Yellowstone…or not.

The last time I ran the statistics for Yellowstone (in 2003), when 23 cougar sightings had been reported from nearly 500 employees and more than 2 million visitors, the odds of seeing a puma were around 1 in 86,000. To put things in perspective, the chances of making a hole in one for an amateur golfer is about 1 in 12,500, for a professional golfer, it’s a bit better at 2,500 to 1. The odds of dying as a result of an automobile crash (based on 2013 CDC statistics) come out to about 1 in 77, and the likelihood of being snuffed out in a volcanic eruption—1 in 80,000. With numbers like these, the prospect of seeing a ghost cat in Yellowstone may lead you to brace for a pyroclastic flow before fawning over a big kitty. Many employees of the Park service and the park’s concessionaire long for a glimpse of a mountain lion and are perhaps only rewarded once in their lifetime, if at all. For those who have had the transcendent experience of watching a lion sprint through the beams of their headlights, the story becomes almost as mythical as the creature itself. Told again and again in hushed, energetic tones, these accounts underlie a certain cultish mystique that hovers around the cat.

Put in enough field time however, and your penny-a-day contributions to the wild cat wishing well can sometimes increase the odds. For those whose business it is to find the great cat, such as hunters, film makers, photographers, and wildlife watching guides, few if any have much luck without the use of dogs for tracking. Cut out the canine factor and the lion’s share of sightings (pun intended?) come down to little more than pure chance. Like close encounters with a grizzly bear (the odds of a physical confrontation with one of those in Yellowstone, should you be wondering, is about 4 million to 1), the more you roll the dice, the more you stand a chance of rolling snake eyes—or grizzly claws. And should you be fearful that the big cat will find you before you find it, don’t worry. In the stronghold of the mountain lion, abundant prey and a healthy fear of humans is enough to keep these cats busy; there has not been an attack on a human in all of Yellowstone history. That being said, they are still predators, BIG predators. As the 31-year-old Colorado jogger Travis Kauffman found out this past February, even a 35-40 pound, 4 to 5 month-old orphaned kitten can be a powerful threat, say nothing of an experienced 180-pound tom. If you recreate in cougar country and have seen one, the odds are, several have probably seen you, and probably from a lot closer than you would be comfortable with. The tracks don’t lie.

Though I have not had the misfortune of being swatted by a bear or a lion, I have seen almost 20 mountain lions during my tenure in the park. Some of these included multiple individuals in a single viewing such as the female lion, her 3 kittens, and a suspected courting male, observed from Hellroaring Creek Overlook. Another ‘multiple’ came from the momma and 2 kittens on Druid Peak in Lamar Valley that inspired my sculpture “Queen of the Mountain,” along with another trio in the Bear Creek drainage of Montana—where we actually saw the mother cougar kill a mule deer and then drag it down into the creek corridor to her 2 kittens. To make this situation even more remarkable, I had the chance to share it with my childhood hero—the Canadian artist, Robert Bateman and his wife Birgit (this also happened to be Bob and Birgit’s first sighting of a cougar in the wild). Several one-off catamount observations such as the one my Yellowstone Association Institute class found along the Tower Fall of the Yellowstone River, which was subsequently observed by many hundreds of people after it took up a bed site on a rock ledge across from some pullouts near Calcite Springs overlook, add to the memorable, but short list of encounters.

Then there was the blustery, white-out day in northern Yellowstone where Jenny and I had forsaken the open valleys in favor of skiing the forested Baronette Ski trail. With savage winds whipping the tree tops above, we shooshed our way upon a 150 lb male cougar feeding on a calf elk below the trail:

When Jenny, skiing a pole-length in front of me exclaimed “there goes a cat,” I was incredulous.

“What!? You mean a bobcat… a lynx, or a mountain lion?”

“A mountain lion,” she said. “And there’s the kill.” She was right.

Having tipped off Wildlife Conservation Society’s researchers to the sighting, and pursuing their promise of pizza and beer, we led them back to the site the next day and participated in the capture. The limited use of tracking hounds was allowed for this purpose and they led the eager blue ticks and redbone hounds via leash close to the site of the elk carcass. The resultant quick chase and treeing served the purpose of minimizing stress to the lion and allowed for a dart gun to hit its mark. As high as the cat was in the tree though, fear of injury should it fall let one of the techs to climb up the tree to the semi-sedated tom and slide ropes around its legs so that it could be lowered safely down. Once the team completed the measurements, and affixed a tracking collar, we were allowed to lay our hands upon the ethereal hunter before the reversal drug was administered; its stout tail of bone and sinew, muscled shoulders and flanks, and it’s supple toe pads and lethal claws left us speechless—we named him Morris.

Another the lone cat logged a place on my list as it was spotted concealing a cow elk that it had killed in the snowy expanse between Hellroaring Creek and the Yellowstone River. Simultaneously, less than a mile away, was the Geode Creek wolf pack and their kill of a cow elk. It was fascinating to watch how each of these two top predators handled the same prey item. The wolves feed voraciously, tearing the carcass wide open and dragging it 50 feet down a slope leaving a crimson smear across the snow for the entire distance; ravens and magpies, coyotes and eagles gathered eagerly en mass. Once full, the wolves left the carcass to the scavengers and lazed about on nearby hilltops like Thanksgiving diners couched in front of the football game following the feast. The cat by contrast, neatly dined alone and once finished, systematically covered the carcass with a pile of snow that it pawed into place like a house cat using the litter box. What birds there were surrounding the cat, took flight under close scrutiny of the lion, then winged directly over to the wolves’ kill (the sculpture “Elevation” came out of that encounter).

The first sightings of anything special are some of the most lustrous gems; a first grizzly bear, a first black bear, wolf, cerulean warbler, elephant seal, bald eagle, mangrove cuckoo, rattle snake, etcetera. My first lion sighting was caught mid-stride on the center line of the road along Soda Butte Creek as Jenny and I motored toward Silver Gate in the northeastern corner of Yellowstone in 2002. Another single cat dashed through my high-beams just east of the Yellowstone Picnic Area (which the Yellowstone Cougar Research team had caught on a trail camera just minutes before it crossed before my lights).

Each encounter is just as alive and fresh as the day it happened; they are just like that—memorable, mesmerizing.

Back on the trail of the cat…

The flurry of texts coming in while yanking on wool pants, gaiters, coat, and backpack only upped my enthusiasm. This kind of reckless departure in the name of cougars has to be tempered against the cold, hard face of reality. Not only do you build yourself up for an over-stuffed let-down, you run the risk of forgetting essential gear (like my gloves in this case). More often that not, we’ll end up missing the big moment despite all of our best efforts: mountain lion sightings are wickedly ephemeral. With wide eyes and longing heart, you typically show up the chosen locale only to be consoled by comments like: “you should have seen it”, “oh, it was beautiful”, “in all my years…,” and, “I never thought I would…” Then at least one in the crowd is happy, usually too happy, to share their photos of what you missed on the back screen of their digital camera. The first reaction is commonly the desire to rip the camera out of their giddy little hands and shove it in a place dark enough to blind a mountain lion. But no, we coo and reply with platitudes and congratulations as we zip up the collars of our coats to hide the gangrenous line of envy creeping up our necks. I crossed my fingers with the hope that this would not be a day of unrequited lion-ness.

Speeding my way to the stepping off point, I got another text.

“Get here quick. Follow my tracks.”

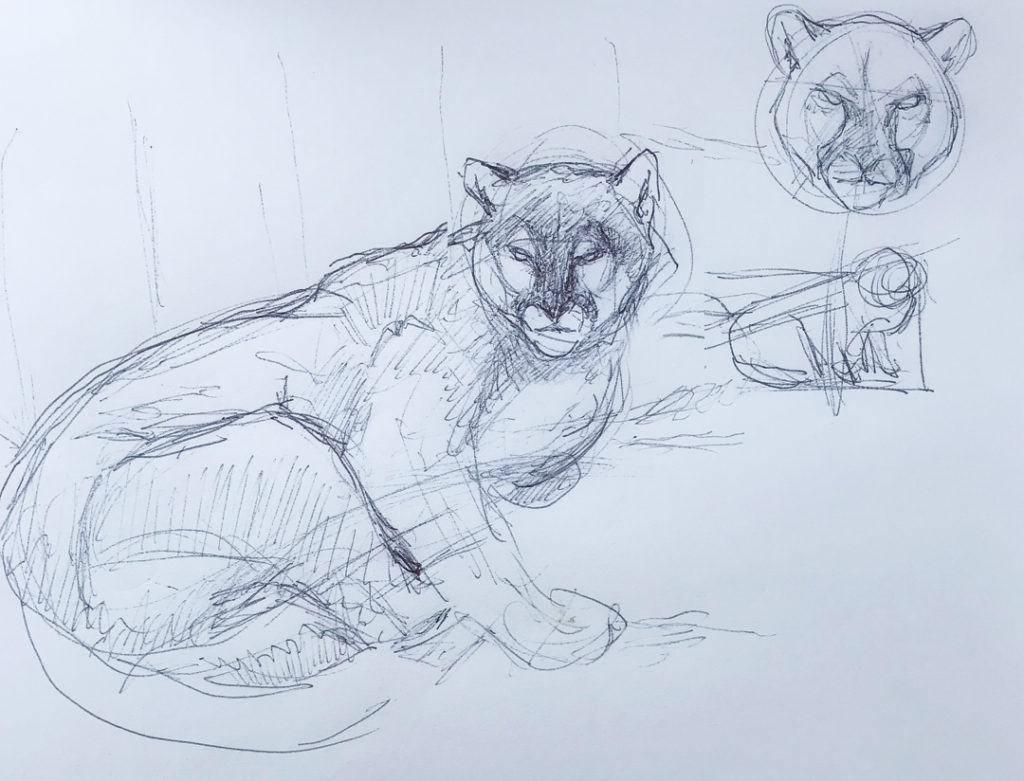

I’m not sure if I closed the truck door or locked it, but the next thing I knew I was running. Yes, literally running as much as one can with a backpack full of gear, heavy boots and a tripod-mounted spotting scope over one’s shoulder. The traverse, albeit relatively flat, seemed to take forever. Though only a mile, the distance was magnified by desire. Then there was the fact that my lungs were about to implode or maybe the reverse, invert and fling themselves outward like a couple of those stupid, roll-up party favors shot into your face at New Year’s party celebrations. I put my head down and just kept chugging. Windswept snow, sugary dry, filled my vision as I strained my eyes to decipher man tracks from those of elk and sheep. The weight of the scope, tripod, sketchbook, extra clothing, camera, lenses, etcetera disappeared, none of it mattered now as I flopped down in the snow, gloveless and out of breath. I just hoped it would still be there… and it was. Bedded beneath a juniper across the drainage was a subtle form bathed in burnt sienna—a mountain lion! I could not be more thankful. Lying on her left side with her feet gathered in a restful pose, her head bobbed with intermittent sleep. This was a cat that had been radio collared and hence was identifiable and a known winter visitor to this area. She looked pooped. Had the toll of nighttime prowling taken its toll? Are cats usually this tired and stationary during this time of the day? It is hard to know—at least from my experience. Having seen so few of them, ‘normal’ is a relative thing when your sample size is not much beyond a bakers dozen. Once I had taken a few photos through the spotting scope, and with my hand wrapped in a sock to thwart the biting cold and frigid northeast wind, I managed to made a few sketches, rejoicing in an extended look at a real, live, wild cougar. The honor of her presence would last for more than 2.5 hours. By the end my body was wanting to join my hands and feet in a collective shiver, but it was worth it.

What are your experiences with Yellowstone cougars? Drop on over to our Facebook page and let us know.