Ravens don’t often volunteer for research positions. This is something that veteran raven researchers John Marzluff and Matthias (pronounced “Ma-tee-us”) Loretto, collaborators on Yellowstone’s newest raven research project, know all too well. From inside of Matthias’ rental car, we look out the windshield in hopes that we might have a taker. At about a half a mile away, one of the inky, black birds takes flight. It banks on stiff wings letting the wind help it gain altitude. Flying above the low hills and sage, its beak points our direction. It sees something of interest. To encourage the raven’s involvement, a roadkill squirrel has been placed in the road off the back bumper of our vehicle. Will it take the bait?

The raven’s eyes lock onto the target. Through my 10x binoculars I can tell that it sees the squirrel—but that’s where it ends. “Ravens are smart, really smart,” Matthias notes. These wary birds have a way of frustrating the daylights out of raven researchers. As I watch, the bird’s behavior shifts ever so slightly, but with a degree of finality. In less than a second, it veers north and lands in an open flat 100 yards away. Passing glances are made in our direction, as the potential recruit waddle-walks among the grasses and bison patties feigning disinterest: The mind of the raven is at work. The change in its demeanor from intrigued to unimpressed is subtle; denoted by a 30-degree turn of the beak when in flight, but the message was clear: “I’d love to, but I just don’t want to.” We both sit back deep into the car seats and exhale, a bit exasperated. To Matthias, however, this is nothing new. As if this sort of cold shoulder wasn’t enough, Matthias has had them buzz his car before at close range, not to examine the bait, but look directly into the car windows as if to say, “I seeee youuu.” Matthias has come all the way from Austria to endure these sorts of putdowns, but is determined to add more individuals to the small handful of birds already captured.

The goal is to have 60 birds online (in accordance with their Park research permit/proposal) for their study to understand the interactions of ravens with wild landscapes and large carnivores. As a post-doctoral researcher from the University of Vienna, Matthias’ work on ravens in the Alps helped earn him grant from the European Union to work at the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior, and to be here today. John, a professor of wildlife science at the University of Washington, is no stranger to the world of corvid research. Author of several books, among them: In the Company of Crows and Ravens, Gifts of the Crow, Welcome to Subirdia, (his newest book, In Search of Meadowlarks is due out in January of 2020) and featured on the PBS documentary TV show Nature in the episode A Murder of Crows, John is widely known for documenting the ability of wild crows to identify individual humans by their facial features, and their subsequent skill at remembering, and also passing along word about who has been naughty and who’s been nice.

Their particular investigations here in Yellowstone hope to explore movements of territorial and non-territorial birds and their use of ephemeral food sources like the kills made by large carnivores, such as bears, wolves and mountain lions. Both of them would like to decipher things like, how exactly is it that thirty to forty of these black scavengers can show up at wolf kill in a matter of minutes? Are there individuals who are wolf scavenging specialists? Are they all expert opportunists, or are they tapped into some, as of yet, unquantified, wireless communications network? This and myriad other questions fuel John and Matthias’ work BUT, the transmitters have to be attached to a bird for all of this to work, hence, our efforts to catch a raven.

Matthias places a newly captured raven into a pillow case prior to transporting it to a nearby banding location.

Whether you are a fan of collaring or tagging animals or not, there are certain questions that cannot be answered without marked individuals. The 35 gram backpack tags placed on these ravens are the size of a matchbox car with 3 short antennae sticking off the back. This small unit is attached with a thin, teflon ribbon harness to maintain natural movement and behavior and can take the observer anywhere the raven goes. I had erronously assumed that ravens set up a territory, staked out their boundaries and more or less stayed put. But the initial data is suggesting that though that does exist, there is much, much more to the picture. And this is the reason we sit in parked cars for hours on end plying the birds with run-over chicken breasts, and suet crumbles, and lurk around bison, elk and deer carcasses. John and Matthias have even held vigil over the Gardiner sewage treatment plant as well—it turns out to be a popular raven hangout (they discovered that the birds consume the frothy oils that rise to the surface of the ponds). They’ve transplanted gut piles from one place to another, created sloppy faux picnicking sites and planted slices of unattended, frozen pizza near unoccupied lunch tables, all in an effort to shed light one the mysterious world of the raven.

Corvus corax is notoriously neophobic. This fear of new things was eluded to by Dan Stahler, a research biologist with Yellowstone National Park, who did his Master’s degree work here in Yellowstone under the renowned raven researcher Bernd Heinrich. During his graduate work here in the Park, Dan found that that “ravens discovered 100% (N = 29) of the observed winter wolf predation sequences on elk… [and for] the majority of wolf kills, ravens were present during the chase sequence and remained at the carcass to feed alongside wolves after the death of the prey.” The longest time it took for ravens to start feeding was about a minute. Conversely, when Dan placed carcasses of his own, say, a roadkill elk, the birds were extremely wary. “Ravens discovered only 36% (N = 25) of the experimentally placed carcasses in the same study region, and did not land or feed despite the availability of unattended exposed meat,” wrote Dan in the summary of his thesis. My own personal observations of ravens in the field tend to confirm this; when something suddenly appears, it can be many hours, if at all, before the rest raven considers feeding. And without wolves to vouch for the authenticity of our offerings, one can easily understand how the capture of just over a dozen ravens has come slowly. None have been netted during my stints at helping and I begin to wonder if I might be the jinx…

John Marzluff (center), Matthias Lorretto (and helpers, including myself, donning a bank robber costume to prevent our raven neighbors from recognizing me in the future), measure, leg-band and tag a raven prior to release.

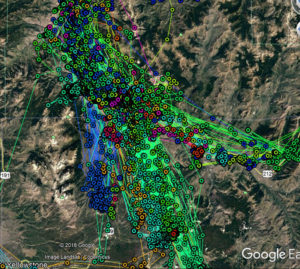

The hassle of enduring failed captures may well be worth the effort though. The initial data coming in is nothing short of revelatory. As it turns out, we have a highly mobile population of commuter ravens—even the territory-holding individuals are making large, repeated movements on a daily basis. Transmitter linkups reveal that birds are leaving the roost in the morning, making a direct flight for distant food sources, then heading back in time to see the sun go down on home ground. In the old days, an antenna-wielding grad student would only be able to tell if the bird was present or not. If it was within range, meaning more or less within line of sight, the metronomic beeping signal would allow one to pinpoint the animal’s location by triangulating a set of directional bearings. If there was no signal, there was no location; the animal was simply AWOL. This newest technology has blown the doors off of not only raven research but has revealed the whereabouts of countless other highly mobile species of birds, fish, mammals, reptiles, and even amphibians. Now, when an animal is inhabiting terra incognita, they can still be tracked, and with surprising accuracy. The bird known to Matthias and John as “Mud Volcano,” an adult male who’s territory is in the area south of Hayden Valley, leaves his namesake home a little after 7am and beelines it for Gardiner—specifically the Eagle Creek drainage, Deckard Flats, and surrounding areas—a one-way flight of approximately 30-miles (Matthias actually used the coordinates of this route in a flight simulator program that lets you fly with “Mud Volcano” over a 3D simulation of the Yellowstone landscape—check it out HERE!). Once there, he often visits the dump, sewage ponds and feeds on remnants of hunter-killed deer and elk. By 2:30pm he is back home defending his fiefdom and settling in for the night; and he’s is not alone. Who would have ever guessed that many of the birds flying over our house just outside of Gardiner are coming from an area 60 or more miles in diameter? Ravens from Tower Falls, Soda Butte, Canyon Village, and Lamar Valley are all doing similar trips to the human hunting grounds each day. Are these movements fueled by individual or collective memory (ravens can live over 2 decades in the wild and have the mental recall to match)? Are these movements just a seasonal anomaly from chance discoveries that are subsequently placed on their annual calendar; and when summer comes will they settle into being homebodies and

dutiful parents again? Could these be learned behaviors passed generationally from parents to young? The questions these observations inspire are limitless. And as of this writing, two birds have taken things even further abroad: one raven caught near Old Faithful started making regular trips to West Yellowstone, Montana and one day took off to Idaho Falls, Idaho for a little while and then changed course, touching down in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. Another bird caught by John in Lamar Valley next to a bison carcass departed for points north, first stopping over around Gardiner, then near Emigrant in the middle of the Paradise Valley and at last check was near Harlowtown, Montana—approximately 100 miles from the tagging location.

To see how widespread some of these patterns actually are, marking another 45 birds would be great, but seems a little bit like wishful thinking. Hoping to lend a hand, I talk Matthias into trying the unconventional approach of a mock hunt, complete with a roadkill deer, donning hunter orange, firing a rifle and field dressing (removing the innards) next to a trap. That doesn’t work either. As it turns out a real gut pile a mile to the north foiled our plans and it was back to the drawing board. What we really needed was a place that the ravens were already comfortable, where we could deposit bait and allow them several days of peace and quite before setting the trap. A historic bone dump near our home and some key connections in the hunting and wild game processing community, were just the ticket. Ensuing days found me heaping meat scraps and bones of elk and deer until the numbers of black scavengers soared. When the day of the first capture attempt arrived, the stage was set.

In the predawn darkness, John and Matthias load the trap and ready the trigger mechanism by the light of their headlamps. A fox barks in the distant darkness. As dawn arrives, magpies erupt in chatter and swarm the bait pile—40 strong. Not long after, their bigger, darker cousins start to amass. Croaks and “kaws,” and the “Hhaaaaa!” sound of feeding calls soon fill the air. The first ravens that land in the meadow linger at a distance. A black semicircle soon grows around the meat and industrious magpies. In their cautious, side-stepping gait, the first skeptical ravens inch toward the food. “One’s on the carcass,” says Matthias. “Now two, three.” The ravens quickly supplant the magpies, and upon seeing their comrades taking the chance to forage, others dive in. “Six, eight, twelve,” the count goes up. And with the press of the remote triggering button, all hell breaks loose. Birds explode in an upwards rush of wings. The lion’s share of the birds fly away, but six of them are now bouncing beneath the net like coal-colored popcorn—this is the most of any single capture event to date for the study (we would later best this tally, so look for the upcoming blog post on how that went down!). Though most wing to freedom, they are henceforth wizened; they will not forget this.

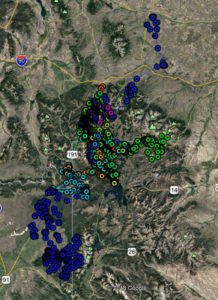

An area heavily trafficked by ravens at the north entrance to Yellowstone near Gardiner and Jardine, MT. The birds are visiting human hunting grounds, the dump and sewage treatment plant.

Preliminary raven locations stretching beyond Yellowstone Park to north of Livingston, MT and Route 90 in the north, and south to around Jackson Hole, WY.

Raven locations spanning the interior of Yellowstone Park north to around Emigrant, MT and east to Soda Butte Creek inside Yellowstone.

We free the birds from the net and place them into cat carriers and pillow cases. Weighing and drawing blood, taking wing and beak measurements also ensues (this helps to discern gender; males have longer, thicker beaks, females weigh 900-1000 grams (about 2.2 lbs) and males a bit more at 1200-1300 grams, and establish relatedness) along with the addition of color coded leg bands and a shiny new locating tag on their backs. Handling these large-beaked birds is a delicate matter—the power of those beaks demand respect. Should you wonder, ravens can bite like a son-of-a-bitch. Even through the cloth handling bag covering their heads, they take the opportunity to mar their captors. As we release the marked individuals, Matthias takes slow motion footage of their release, and the transmitters begin their work. At every preset time interval (anywhere from 5 minutes to every hour) from here on out, the marker tags will be beaming information to the researcher’s laptops via cell tower connections and their own mobile antennas and documenting their travels. There are some new tools in place to learn, may we use them wisely, and now let the ravens be our teachers.

**additional posts will be logged about the study both here and on Facebook—stay tuned and learn along side us!**